By Valentina Montalto

Provided that culture uniquely defines a city, which urban contexts are more culturally vibrant? And in which ones does culture drive creative economies? This study presents a novel and freely accessible dataset – the Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor – gathering 29 indicators for 168 European cities. Capitals generally lead on ‘Creative Economy’ but non-capitals do better on ‘Cultural Vibrancy’.

In the past decade, the promotion of culture and creativity has steadily gained momentum in urban policy-making circles, putting cities at the forefront of the culture-led development notion. Urban areas, especially in Europe, indeed gather most of our built heritage but also enable the development of creative economies thanks to agglomeration advantages and networking effects. Culture in cities exerts an important attraction power on talents, visitors and citizens and boosts innovation in many knowledge-led sectors, from ICT to tourism.

Nevertheless, the practical implementation of culture-led development strategies remains a challenge. Among other reasons, this is related to the fact that culture is multidimensional, covering different domains of the economy, society and individuals’ lives. Culture-oriented actions require wide-ranging analytical frameworks measuring the diverse sets of cultural resources that can be mobilised for development purposes and their varied impacts on the economy and society.

The lack of proper monitoring structures basically revolves around two main arguments: on the one hand, the difficulty of defining and delimiting culture, and, on the other, the lack of suitable and comparable data.

This study tries to challenge the status-quo by adopting an evidence-based approach to definition(s) and measurement attempts: while considering culture a multifaceted urban phenomenon, difficult to be mirrored in a prescriptive definition, attention has been placed on (some) meaningful aspects that can empirically be measured by making the most of available data, which come from both Europe-wide official statistics and ‘experimental’ web-based sources.

In this vein, a new culture-specific dataset – the Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor (CCCM) – has been developed, building on a detailed review of 36 existing indices and expert consultation. The CCCM gathers and makes available online 29 carefully selected indicators for 168 cities in 30 European countries. They measure the presence and attractiveness of cultural venues and facilities (Cultural Vibrancy), the capacity of culture to generate jobs and innovation (Creative Economy), and the conditions enabling cultural and creative processes to thrive (Enabling Environment).

Table 1 The Cultural and Creative Cities’ Monitor: conceptual framework, indicators and weights

Interestingly enough, the data analysis reveals that in fifteen out of twenty-four countries (63%), non-capital cities, mostly medium-sized, outperform capitals on ‘Cultural Vibrancy’. This finding is certainly influenced by the methodological choice of expressing most of the indicators in per capita term. This approach is primarily intended to enable cross-city comparability but also rewards smaller cities, which ultimately seem to have ‘more’ than larger cities in terms of cultural infrastructures per inhabitant. At the same time, this finding confirms the multi-centric structure of Europe: while some European countries are indeed very much polarised around the capital city (e.g. Denmark, France, Portugal), many others are rather multi-polar (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Spain) – a trend that is very much reflected in these results.

Fig. 1. Cultural Vibrancy: Ranked cities and related scores within EU Member States.

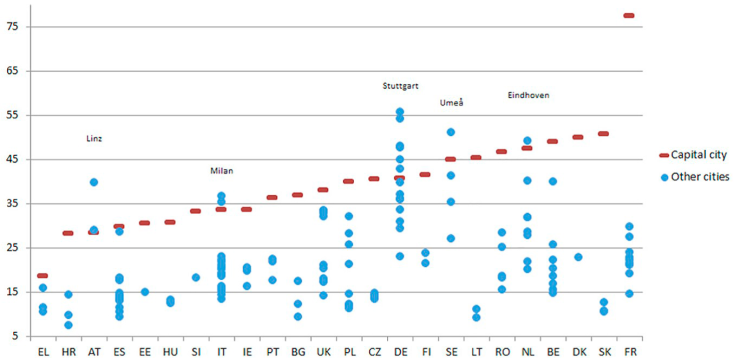

An inverted pattern is however found when looking at the ‘Creative Economy’ indicators. In this case, and probably not surprisingly, capital cities not only obtain the highest score in nineteen out of twenty-four countries (nearly 80%) but they also perform considerably better than non-capital cities in most countries. Cultural, historical, economic but also methodological factors may help explain the observed exceptions. In Italy, for instance, agglomeration advantages have historically been found in Milan which, together with Rome (just a few points behind), represents a major cultural and creative economy hub. A closer look at the indicators underlying the ‘Creative Economy’ domain can instead better explain the results for Austria, the Netherlands and Sweden. Generally speaking, while the capital cities have a more balanced score across the board, ‘winning’ cities rather excel on one single indicator which boosts the overall score. In Sweden, for instance, Umeå obtains the maximum score (100) on the annual number of jobs created, mostly due to the city’s fast growth of the last decades. In the Netherlands, Eindhoven is particularly strong on innovation outputs (100) compared to the capital, Amsterdam, most likely due to its renowned and prolific high tech- and design-led environment. In Austria, Linz conquers the first place thanks to its very high share of cultural and creative jobs per capita, but it is the capital city of Vienna that registers a better capacity to create jobs in the creative economy.

Fig. 2. Creative Economy: ranked cities and related scores within EU Member States.

Despite the methodological problems always inherent in capturing a complex concept like culture, the collected data show that diverse sets of cultural resources and enabling factors can be mobilised for targeted investment efforts by different typologies of cities. Although capital cities and metropolitan areas predominate in terms of creative economy performance, the literature shows how policy interventions can circumvent geographic determinism (Krugman, 1991, Meijers and Burger, 2017).

The data presented herein can be used and complemented by scholars to address policy relevant questions. For instance, which cultural legacies or institutional factors may explain differences across cities? How does culture affect the ‘rest’ of the urban economic environment and individuals’ well-being? Do residents have the same opportunities to access culture and build cognitive skills within European cities? Do best scoring cities share common features in terms of policy governance and actions?

With cities playing a growing role in the provision of public services and being the recipients of increasingly larger transfers – especially at the European level through the EU cohesion policy funds – the data presented here can also serve as an initial tool of empirical assessment to identify ‘development gaps’ where funds should be allocated.

The article is based on:

Montalto, V., Tacao Moura, C. J., Langedijk, S., Saisana, M. Culture counts: An empirical approach to measure the cultural and creative vitality of European cities, Cities, vol. 89, June 2019, pp. 167-185.

About the author:

, Joint Research Centre of the European Commission.

Image source:

ArTo – stock.adobe.com