By Chiara Dalle Nogare and

The recent narrative on museums as catalysts of innovation considers their relations with other cultural and creative industries to be very important. To verify this claim, we propose a conceptual framework qualifying these relations as either strong, moderate, or weak links, according to their potential in terms of knowledge spillovers from museums to the CCIs. We apply this classification to data collected from Polish museums. Our findings indicate that strong links are outnumbered by moderate and weak ones.

The role of innovation in fostering economic growth is well established in macroeconomics, and recent contributions highlight that creative professions may play a role in making a nation or a region more innovative, see evidence by Cerisola (2019) here and Rodriguez-Pose and Lee (2020) here. This is different from saying that the cultural and creative industries (CCIs hereafter) play a special role in the innovation ecosystem. Yet policymakers often translate scholarly evidence on the impact of creative professions into agendas focusing on the CCIs, which, according to most scholars, include museums. Museum directors are often invited to favour interactions with the other CCIs, in hopes of making the latter more innovation-prone. As CCI firms are said to be good at exporting innovation to the other economic sectors, this should also enhance innovativeness in the wider economy.

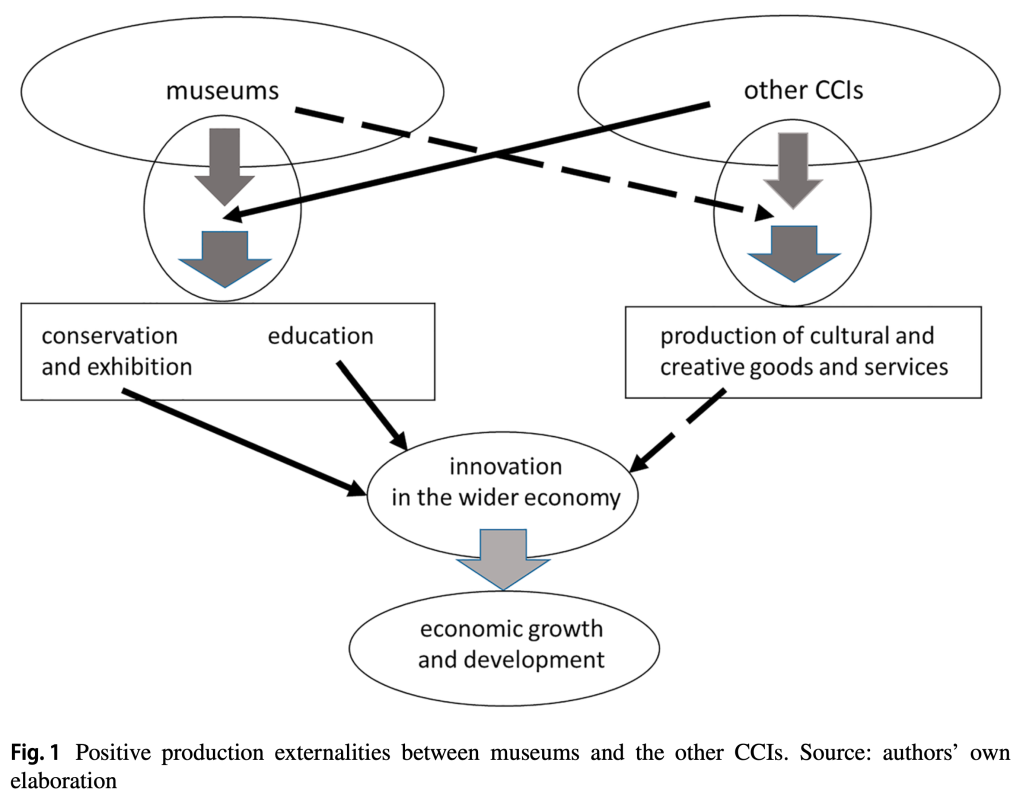

As we illustrate in our contribution, CCIs’ higher ability in exporting innovation has not been confirmed by robust empirical evidence, yet. However, fostering innovation within the CCIs may be a policy goal in itself, so we concentrate on the question whether museums are catalysts of innovation in the other cultural and creative industries. Following Throsby (2008), we define the CCIs as follows: contemporary visual arts and photography; performing arts; music; the book and publishing industry; the radio, TV and film industries; internet portals and the press; the advertising industry; design, architecture and fashion. We take our definition of economic innovation from the Oslo Manual, which includes scientific and technological as well as organisational, financial, and commercial changes that make firms more competitive, because they introduce novel approaches to production and markets. The conceptual framework we propose is illustrated in this figure.

The vertical ovals represent museums and CCI production functions. Museums’ contributions to innovation through their core missions (solid arrow), sometimes involving the CCIs, should not be overlooked, but this is often the case. The focus is on the dashed arrow, representing the positive externalities of museum production associated with project-based cooperation and supply chain linkages between museums and the CCIs. As an example of the former, think of designers and artists-in-residence programmes; as an example of the latter, think of a museum commissioning a new building to an architect. In both cases, there is potential for the creation of new content, of an innovative reinterpretation of existing content, or of new ways of conveying content. These stem from long exposure of CCI creatives to the museum’s collection and/or to the expertise of museum staff. But are all the relations between museums and the other CCIs just as rich? Certainly not. Especially in the case of supply-chain linkages, there may be little or no knowledge spillovers associated with networking with museums. Think of museums’ rental of spaces to CCI firms and institutions, or museums’ purchases of advertising space. Indeed, the main point of our contribution is to clarify that the CCIs may become more innovative through engagement with museums only if, thanks to this networking, they can benefit from knowledge spillovers. In fact, it is the presence of knowledge spillovers what makes infra-industry relations conducive for innovation as argued by Bakhshi and McVittie (2009).

The way we elaborate our point further is the following. We propose a taxonomy of museum-CCI cooperation modes, distinguishing between those potentially rich (strong links) and those likely to be poor in knowledge spillovers (weak links). Poland is a national context where the role of museums in regional and local development has been increasingly recognised in recent years, and for which a unique dataset on the types of relations formed between museums and the other CCIs is available. We therefore apply the above mentioned taxonomy to the data collected from 261 Polish museums on their activities in the 2017-2018 reporting period. Our aim is not only to show what links Polish museums have with the CCIs but to consider the quality of these links. Our analysis leads us to conclude that although most Polish museums have relatively frequent exchanges with CCI firms and institutions, weak links outnumber strong ones. This statement refers to relations with all CCI sub-sectors. For instance, Polish museums often cooperate with the music industry (66.7%). However, this is occasional cooperation in the vast majority of cases (57.5%), and most importantly, its aim is the dissemination of existing creative content or providing opportunities for promotion and additional earnings to the sector rather than inspiring new artistic creation. Very few museums (1.5%) commission music compositions and recordings. Rarely (0.8%) do they provide information and access to items in the museum collection that could inspire contemporary music endeavours (e.g. the possibility to perform on historic instruments, or providing access to historic music recordings or scores). This does not conclusively prove but certainly suggests that, at least in the Polish context, the contribution of museums to innovation through their relations with CCIs is not particularly strong.

Clearly, there is a more direct way to assess whether cooperation with museums induces the CCIs to become more innovative, namely, to estimate a model where some measure of innovation for the CCIs is the dependent variable and the presence of a CCI–museum relation is a covariate. To our knowledge, however, there have been no surveys so far investigating the innovative products and processes of CCIs in the context of their cooperation with museums. Our recommendation for this future research agenda is to consider the right explanatory variable: what matters is not how many relations the investigated CCIs have with museums, but the number of strong links. In this respect, our taxonomy of museums-CCIs relations may be useful. It may also be a point of reference for policymakers wishing to support museum-CCIs interactions within an innovation policy framework, because it singles out the types of interactions with some real potential in this respect.

About this publication:

Dalle Nogare, C., Murzyn-Kupisz, M. Do museums foster innovation through engagement with the cultural and creative industries?. Journal of Cultural Economics (2021).

About the authors:

Chiara Dalle Nogare is Assistant Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics and Management at the University of Brescia.

is Associate Professor in the Department of Regional Development at the Jagiellonian University.

About the image:

Dresses designed for a fashion design competition for young designers organised by the Museum of King Jan III Palace in Warsaw displayed in museum interiors, photo: M. Murzyn-Kupisz.