By Juan de Lucio &

We listen to music every day. It is our companion when we travel and enhances the emotions of our favourite movie scenes. Whilst it may act as the life and soul of a party, music can also accompany us in our gloomier moments. At any point of time, we choose what music matches our mood. In this study, we explore how musical preferences change when macroeconomic conditions change. The results show that musical preferences adapt to smooth out fluctuations in social welfare (SWB) related to business cycles; for example, society prefers positive music in recessions.

Macroeconomic conditions have an impact on subjective well-being (SWB). Music is the most important source of consolation as compared with other soothing behaviours (Hanser et al., 2016). We show that culture, specifically music, adopts a role in balancing SWB across upturns and downturns. This is a sort of lipstick effect: the increase in the consumption of some goods (for instance, cosmetic products) during recessions in order to improve self-esteem or find personal satisfaction through cheap indulgences rather than expensive pleasures (Hill et al., 2012). In the culture sector, this effect has already been tested via theatre attendance (Tajtakova et al., 2020). We provide evidence on the music sector, which is more accessible and provides more immediate satisfaction than other cultural services. Understanding the relationship between music and SWB provides the empirical fundamentals aimed at protecting cultural policies specially during recessions.

Figure 1 – Relational structure

To show this relationship, see figure 1, we gather the lyrics of the songs listed on the Billboard Hot 100 weekly chart for the period 1958-2019. This collection includes 28,747 songs over 3,205 weeks. This dataset reflects society revealed preferences. To quantify the music choices, we use Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to build indicators which collect the positiveness (and negativity) of music preferences for each week. These techniques have already been tested in the music field. Borowiecki (2017) uses the letters written by three famous composers to measure their creativity in terms of the negative emotions expressed in said letters. Palomeque and de Lucio (2021) prove that music and lyrics offer complementary but different information.

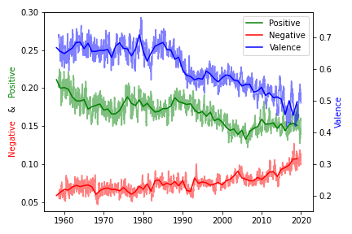

Figure 2 exhibits the evolution of these indicators as well as the valence indicator (a coefficient calculated by Spotify that measures how positive a song is as regards its musical characteristics). Over the whole period, a downward trend is observed in those indicators related with the positiveness (and valence) of the most consumed songs and an upward negative tendency for the most consumed lyrics.

Figure 2 – Positive, Negative and Valence preferences time series

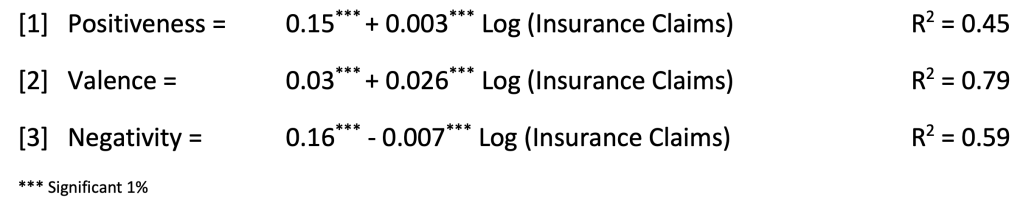

We test how these indicators change in line with the macroeconomic conditions. The reference equation and estimated parameters are presented in figure 3. Unemployment is the variable with the most impact on SWB (Deaton, 2011; Frey & Stutzer, 2010; Mertens & Beblo, 2016; and Wolfers, 2009). Unemployment insurance claims reflect short-term economic conditions. When insurance claims rise, positive music preferences and valence also rise (positive parameters of equation [1] and [2]), but the preference for negative songs decreases (negative parameter in equation [3]). This means that, when macroeconomic conditions worsen, people turn to music in order to cheer themselves up.

Figure 3 – Estimations

Some other variables such us inflation, the interest rate and the stock exchange have similar effects on music, see de Lucio and Palomeque (2022). We observe that this effect is mainly short term: the impact of the recession slowly fades out over time. In the full paper the results for all these variables are observed, including different dimensions of unemployment or the effect of the length of the recession cycle. Moreover, results are independent of the way in which we build the indicators.

The conclusions of the paper are clear: people use music to regulate their SWB and they react when downturns make them sadder. The effect is bigger for negative music preferences, which tend to decrease more compared to the rise in positive music preferences. The results are robust considering both lyrics and musical characteristics. Results also work for weekly, monthly, and annual data and for different macroeconomic variables. From an economic policy point of view, we consider that said results serve to foster the promotion of the supply of culture diversity in guaranteeing specific societal needs. Also, access to culture should be facilitated. Sadly, although the recovery of SWB can actually support the recovery of an economy, during recessions it is more common for policy makers to dismiss culturally related policies and funding. This study opens a new field full of possibilities: does this self-regulation mood through music work in all countries or is it a characteristic of a particular culture? Do songs achieve more success when expressing a particular mood under a specific set of macroeconomic circumstances? What conditions, other than macroeconomic ones, modify music consumption mood preferences?

References

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2010). Happiness and economics. Princeton University Press.

Palomeque, M. & de Lucio, J. (2021). El sentimiento de las letras de las canciones y su relaciòn con las características musicales. Procesamiento del Lenguaje Natural, 67(67).

About this article

De Lucio, J & Palomeque, M. (2022). MUSIC PREFERENCES AS AN INSTRUMENT OF EMOTIONAL SELF-REGULATION ALONG THE BUSINESS CYCLE. Journal Cultural Economics.

About the authors

Juan de Lucio is Professor of Economics at Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain.

is PhD Student at Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain.

About the image

The photograph shows a happy woman listening to music. The photo was taken by Yaroslav Shuraev and it is right free at pexels.com.

Leave a Reply