By Ruth Towse

What are the relative roles of copyright law and market forces, especially when they are altered by disruptive technologies? The paper takes an historical approach to the development of music publishing viewed through the lens of present day issues, in particular the impact of digitisation in the creative industries.

The history of copyright in music and of music publishing shows that just having rights is not enough: it requires the appropriate business models to exploit them. Conversely, the enactment of rights alone cannot stem market forces; music is a consumer good and consumer choice rules this market. The switch in the consumption of music to mechanical and now to electronic technologies necessitated the adoption of a new business model.

The beginnings of copyright

For centuries, the business of music publishing consisted of the acquisition of the copyrights of musical compositions by composers and song writers, organising the printing, publication and sale of sheet music and the printing and hiring of scores and orchestral parts for theatrical and concert performance. Theatrical rights—the grand rights—relating in particular to opera were organised by arrangement with the promoter or impresario and are not dealt with here. Copyright law in the UK dates back to the 1710 Statute of Anne, conferring on the author the exclusive right in her work, but it was not deemed to apply to musical works until 1777. For many years thereafter, however, poor drafting of the law and difficulties in its enforcement enabled piracy of sheet music to flourish alongside the growth of the legal business. The Copyright Act of 1842 protected the sole right of reproduction for musical works but failed to provide summary penalties for misappropriation of copyright and proceedings for damages had to be pursued through the civil courts. It was not until the 1906 Musical Copyright Act that the publishers succeeded in eliminating large-scale piracy. By the early years of the twentieth century, however, sales of sheet music to the public, the main source of music publishers’ revenue, were declining. The main appeal of the pirates lay entirely in undercutting the price of ‘legal’ copies, usually with considerably inferior quality since the only means of mass reproduction was to set up the printing process all over again but with cheaper materials. As with unlawful copying of CDs in the 2000s, the question was asked why the relatively high prices charged by music publishers were not reduced to compete with the pirates.

What was the role of copyright in the market for published music?

Copyright protects composers as they seek to exploit their works but to do so, and they inevitably have to contract their rights to a publisher, for whom the acquisition of the copyright becomes an investment in a profit-making business.[1] Copyrights consequently became the assets of music publishing.

The big change in the orientation of music publishing at the turn of the twentieth century, amplified enormously at the turn of the twenty-first, has been that musical works are no longer used only by people to whom they were sold or hired. Through new media, recorded music has become widely available in secondary markets, in broadcasting, public performance in a multiplicity of venues, on social websites and so on. Appropriation of revenues from these uses required collective rather than individual action. Somewhat late in the day, music publishers recognised the value of performing rights and formed institutions for collective rights management, which they all eventually joined, enabling the cost-effective system of blanket licensing to prevail.

Collecting societies now exploit rights on a global scale through international agreements and, increasingly, through one-stop-shop multi-territorial licensing. Besides the cost of managing millions of transactions of digital usage of music, multi-territorial licensing requires considerable investment in new data systems. A shift to individual licensing could undermine the bargaining power of the collective rights management system which supports smaller enterprises and creators—essentially the same problem faced by the Performing Rights Society in its early days (a case of history repeating itself?). Nevertheless, the management of musical rights will continue to be the main source of revenue for composers and publishers.

The paradigmatic shift from the sale of printed music to exploiting and managing musical rights that took place in music publishing during the early years of the 20th century was due to the changing market conditions rather than to changes in copyright law, which followed them. Music publishing in the UK continues to be a profitable arm of the wider music industry. It has not been so vulnerable to online piracy as has the record industry. Though it has suffered from considerable reductions in recorded media fees, the switch of consumers from downloading to streaming music has raised online revenues. Foreign licensing is now the biggest single source of Performing Rights Society revenue, though it is falling.[2]

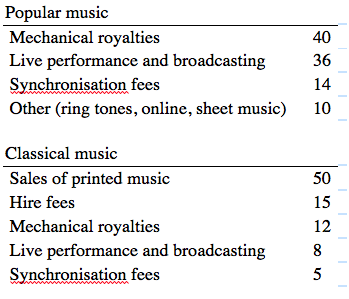

Table 1. Percentage of revenues from various rights and sources: popular and classical music, 2012

Source: MPA (unpublished)

On the one hand, copyright law was ineffectual in controlling piracy throughout the 19th century and on the other hand, performing rights were ignored by music publishers for over 70 years; these points suggest that copyright was not the main reason behind the success of the industry. Music publishers adapted their business models only when new streams of income from new forms of exploitation through sound recording, broadcasting and film became available as a result of technological progress.

Economics of music publishing: copyright and the market is one of several papers on music publishing emanating from the project ‘Economic Survival in a Long Established Creative Industry: Strategies, Business Models and Copyright in Music Publishing’ (AH/L004666/1) funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Board at Bournemouth University.

This article is based on:

Towse, Ruth. 2016. Economics of music publishing: copyright and the market. Journal of Cultural Economics.

Author Information:

Ruth Towse is Professor of Economics of Creative Industries at Bournemouth University. She is Fellow in Cultural Economics at CREATe at the University of Glasgow.

[1] Caves, R. (2000). Creative industries. Contracts between art and commerce. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

[2] Samuel, M. (2014). Winds of Change. Journey of UK Music from the Old World to the New World. Review of Economic Research on Copyright Issues, 11(2), 27–59.

Image:

‘The old year has passed’, hand written manuscript for organ by J. S. Bach (BWV 614), 1708-1717. Public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply