By Joanna Woronkowicz and Douglas Noonan

Why do workers earning wages or salaries decide to become self-employed, and are artists like other professionals in this regard? Artists “go freelance” more than other professionals, especially during the Great Recession. Freelancing artists resemble other professional “independent contractors,” but differ involving education, urban locations, and families.

The entrepreneurial potential of artists is well-known. Not only are these workers more likely to be self-employed than other types of professional workers, but the kind of work they do is often aligned with work done in an entrepreneurial setting. For example, we rely on artists to create new forms, and give meaning to otherwise ordinary events, just as we rely on entrepreneurs to offer new goods and services in the market economy.

Despite the natural alignment between artists and entrepreneurs, not all artists work as entrepreneurs. Or, more specifically, not all artists are self-employed. Given that self-employment is often the clearest route to entrepreneurship, and that artists often define self-employment as their ultimate end goal, we were motivated to find out what influences artists to switch to self-employment. This is particularly interesting in light of the much-hyped emergence of the “gig economy” with its emphasis on temporary, flexible, independent-contractor positions in recent years

Using panel data from the 2003 to 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS) in the United States, we set out discover the factors that contribute to artists’ transitions from paid employment to self-employment. We defined artists based on Standard Occupational Codes listed in Table 1. The CPS is conducted by the US Census Bureau monthly and collects employment data on a representative sample of US workers. Most previous analyses using CPS data examine it one year at a time, but we reformatted the data to be able to observe worker transitions from one year to the next (over a total of 13 years). Connecting the same worker from year-to-year allows us to make potentially causal claims, notwithstanding the limitations from only observing each worker for just two years.

Table 1. List of Standard Occupational Classifications (SOC) Codes and Arts Occupations

Even the basic statistical description of artist employment is revealing, particularly the rate of self-employment, labor force participation, and unemployment. We also examined the transition rate among artists and other professional workers. Some highlights related to the descriptive findings include:

- Artists are much more likely to be self-employed than other professional workers.

- The self-employment rate among artists increased between 2003 and 2015, while the rate decreased for other professional workers.

- There was a marked increase in the self-employment rate among artists between 2008 and 2011 – the period known as the “Great Recession.”

Regarding this last point, we found that the number of artists in the labor force declined between 2008 and 2011 suggesting that the rise in self-employment among this group was partly a function of a lack of job opportunities.

Finally, we found that artists have a disproportionate “churn through” rate compared to other professional workers. In other words, artists are much more likely to move in and out of self-employed arts work than other professional workers are to transition in and out of self-employed non-arts work.

Next, we conducted regressions that predicted transitions to self-employment from paid employment based on an array of factors cited in the entrepreneurship and cultural economics literatures as being potentially influential. These included the usual suspects like income, gender, and education level, but also influencers that might only apply to artists such as whether the worker lives in a city, and if a city has a large concentration of artists. Some highlights from the statistical analysis include:

- Artists share many of the same characteristics as other professional workers in terms of what influences them to switch to self-employment. For example, gender, marital status, and education status matter for both groups in terms of who decides to switch to self-employment and who does not. For example, married females with higher educational levels are more likely to switch to self-employment than single, low-educated males.

- However, demographic characteristics, such as age and gender, matter less in terms of predicting who transitions to self-employed arts work than for all other professional workers.

- Educational levels affect an artist’s propensity to switch to self-employment even more than income does.

- Artists living in cities, particularly cities with higher proportions of artists relative to the total workforce, are more likely to transition to self-employment than artists living in non-urban areas.

- Married females are more likely to transition to arts-related self-employment than other groups, suggesting that family support mechanisms are important to enabling entrepreneurship for some artists.

To conclude, this research emphasizes the need to understand individual occupations’ unique characteristics related to transitions to and from self-employment. Policies designed to stimulate entrepreneurship could benefit from more tailored approaches based on a better understanding of why specific types of workers transition. Recent work in entrepreneurship and cultural economics has proposed artists and entrepreneurs as key contributors to regional economies. It also appears that certain regional economies contribute to artists’ becoming entrepreneurial. This work, and future work, can add to these discussions by giving us a better grasp of exactly what it means to be an artist entrepreneur.

This article is based on:

Woronkowicz, Joanna and Douglas Noonan (2017) ‘Who Goes Freelance? The Determinants of Self-Employment for Artists’ in Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice. Published online 29 September 2017.

This study is funded in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

About the authors:

Joanna Woronkowicz is Assistant professor in the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University in Bloomington.

Douglas Noonan is Professor of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

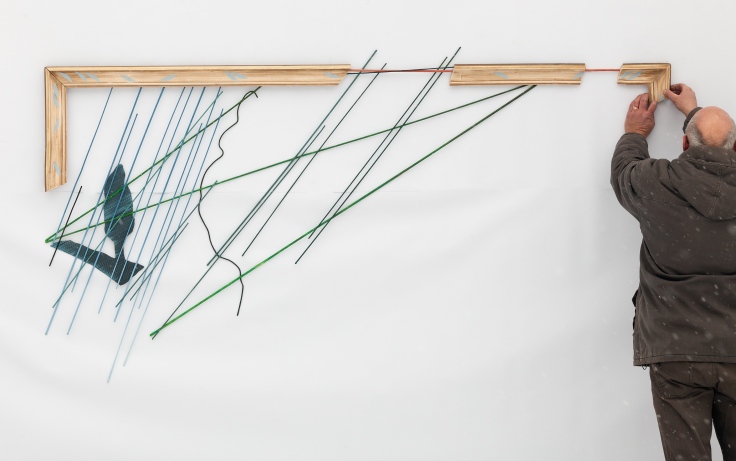

About the image:

Jiří Kubový working (2013) on Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply