Christophe Spaenjers, William N. Goetzmann and Elena Mamonova

When Pablo Picasso’s “Les Femmes d’Alger (Version O)” sold at Christie’s in New York for $179 million dollars in May 2015, it was only the 36th time in the past 315 years that a world auction record had been set, and the sale raised questions well beyond the art world. How could a single painting be worth so much? Why is art so important to wealthy households? What economic and social factors could lead to enshrining Picasso’s colourful near-abstract portrait as the most valuable picture in the history of the modern world?

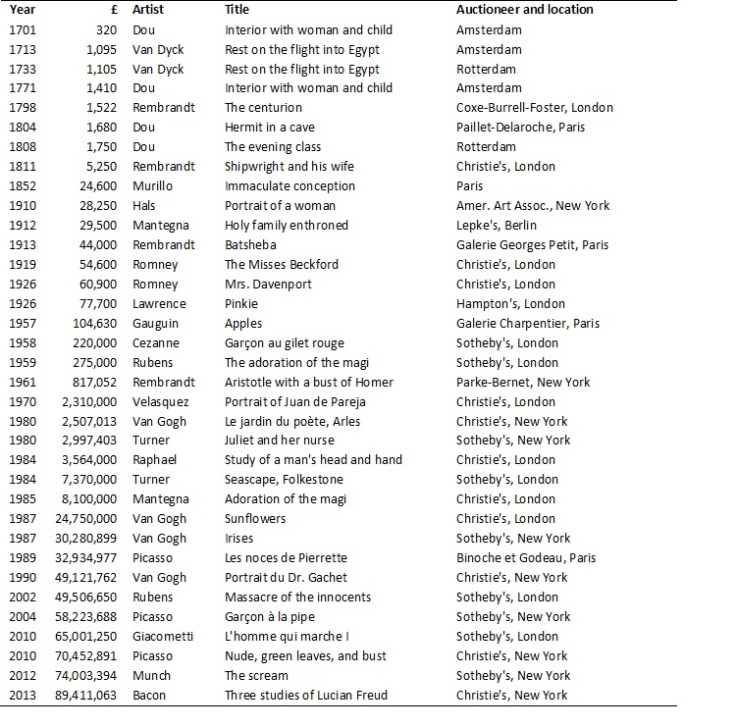

In our paper “The economics of aesthetics and record prices for art since 1701”, we trace all record-breaking art auctions (in nominal British pounds) since the start of the eighteenth century that preceded the Picasso sale. The table below shows the details for these 35 sales.

An in-depth study of these record-breaking sales shows that art prices and tastes are not separable from fluctuations of wealth and power. The paradox of the art market is that objects created for personal and contemplative aesthetic enjoyment are connected to the broader social fabric through an economic transaction. We can broadly distinguish four periods over our time frame.

An in-depth study of these record-breaking sales shows that art prices and tastes are not separable from fluctuations of wealth and power. The paradox of the art market is that objects created for personal and contemplative aesthetic enjoyment are connected to the broader social fabric through an economic transaction. We can broadly distinguish four periods over our time frame.

1700 – 1850

In this period, French and British fascination with Dutch art drives modest little pictures by Gerrit Dou to world record auction prices three times in a century. We also witness the emergence of Rembrandt as the definitive Old Master—a strategic equilibrium in taste that would last into the mid-20th century.

At the same time, art becomes a means of acquiring both international and domestic power. The Napoleonic Wars not only disrupt the prevailing aesthetic norms but introduce a new paradigm of acquisition and possession. Catherine the Great of Russia uses collecting to raise respect for Russia among the European states. She sets a record for a Dou painting in 1771 only to lose it in a tragedy at sea; sunken in a Finnish port where it remains today, awaiting recovery.

1850 – 1930

The decades around 1900 are a period of global financial and economic market integration and vast shifts in world population. It is a time when nouveaux riches buy culture—the taste and trappings of the Old World—through internationally-operating dealers. Duveen convinced American millionaires to buy sweet paintings evocative of British privilege: Romney’s “The Misses Beckford” and Lawrence’s “Pinkie” both set records in this era—and these records are the wholesale prices paid by Duveen before he resells them. Competitiveness figures prominently in the Gilded Age; the sometimes ordinary nature of the artworks themselves is a reflection of the fact that winning—and even setting a record—is as important as the prize.

1930 – 2010

The Great Depression and World War II have a profound effect on the market and on taste. No price records are set until 1957, but then we start seeing a shift in market leaders towards Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. While an occasional Velasquez or Mantegna still sets a record, exquisite taste begins to be characterized by an appreciation of complex and increasingly abstract images.

The period from 1957 to 2010 witnesses an extraordinary boom in art prices. By some measures, art beats even the exuberantly recovering equity markets from mid-century forward, with increasing public interest in speculation as well as collecting. A second era of globalization also hits the art market: after Japan booms in the 1980s and Japanese property prices rise to the stratosphere, Japanese buyers set three records with purchases of two Van Goghs and a Picasso. Art in this period is increasingly recognized as a financial asset.

Beginning in the late 20th century, auctions become glamorous events for the high society, while in the decades before they were rather dull events for art market professionals. This is a significant evolution that turns the auction room in an arena for social competition. Auction houses re-invent themselves as luxury goods companies rather than simple intermediaries in the art market. Some of the record auction sales in the late 20th century tell a tale of social aspiration: wealthy people who use the calling card of a highly visible acquisition as a social entrée. Also in this period, as records are set with increasing frequency, most museums are priced out of the market.

As fine art grows more valuable, it is recognized as a highly portable store of value—and the auction as a public means of creating that value. Record-breaking prices paid at auction have much broader economic consequences: when a van Gogh sells for a record price, all van Gogh collectors mark up their personal asset value.

2010 – present

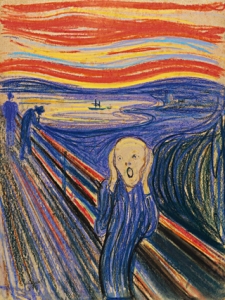

Stylistically we see a shift towards defining 20th-century Expressionism as a new “blue chip” style. Munch, Giacometti, and Bacon set new high-water marks for auction sales, and in doing so broaden the pool of art that defines the ultimate collectors. This shift is coincident with the rise of auction sales in China. At the time of writing, a work by a Chinese artist has not yet set a record price, but this will likely happen as China (like Russia in the 18th century) views art as a dimension of national competition, and Chinese land prices (like Japanese land prices in the 1980s) drive up fortunes.

This article is based on:

Spaenjers, Christophe, William N. Goetzmann, and Elena Mamonova. 2015. The economics of aesthetics and record prices for art since 1701. Explorations in Economic History. DOI: 10.1016/j.eeh.2015.03.003

Author information:

Christophe Spaenjers is Assistant Professor of Finance at HEC Paris.

William N. Goetzmann is Edwin J. Beinecke Professor of Finance and Management Studies at Yale School of Management.

Elena Mamonova is an alumna of the Yale School of Management.

Image:

P. Picasso: Les femmes d’Alger. Source: Christie’s, http://www.christies.com/features/Picasso-5829-1.aspx.

Leave a Reply