By Victoria Ateca-Amestoy, Javier Gardeazabal and Arantza Ugidos

There is a very scarce tradition of cultural policy evaluation. Many public programs are devoted to increase cultural access by means of direct or indirect funding of cultural activities, targeting either consumers or producer. In this entry, we comment on the causal inference analysis that we did of the 2012 VAT reform for cultural services and its effect on household’s participation and expenditure.

Granting equal access to cultural goods is one of the objectives of the Spanish political system. Though in a minor position, it is explicitly considered in the 1977 Spanish Constitution (Art. 44). As in any other country, there is plenty of evidence that cultural participation is by no means equalitarian in our country, so any public policy should try to enhance cultural participation or, at least, not prevent too many people from accessing to cultural contents.

The financial crisis that preceded the public sector deep crisis in Spain in the early 2010s left Spanish households in a very precarious condition. According to official figures by the Spanish Statistical Office, in the third quarter of 2012, unemployment reached a (then) record 27.2 per cent, and average household income had accumulated a 7.65 per cent reduction since 2009. In that context, the Spanish Government announced a reform of the Value Added Tax to be implemented in September 2012. The reform was based in the increase of VAT tax rates and the reclassification of some categories of goods and services from reduced tax rates to the general rate. This implied that the VAT rate for cinema tickets, performing arts and cultural live events went from 8% to 21% (13 percentage points), while the general VAT rate increased from 18% to 21% (just 5 points). As a consequence, the prices of cultural services increased sharply, as shown in Figure 1, and, in relative terms, i.e. when compared with the representative basket of goods and services that is represented in the Consumer Price Index, it even increased more.

Figure 1:

The reform, implemented by the government of the Conservative Party in power, was taken as a big offense by the cultural sector, specially by the cinema industry that perceived it as a revenge because of having been traditionally critic with Conservative administrations. The increase in the so-called “cultural VAT” was heavily contested and gained huge visibility in the media. Some cultural organizations anticipated the sale of seasonal tickets and annual subscriptions to the weeks before the increase, while there were also creative individual responses that ranged from the campaign of a theatre company to sell carrots (taxed at 4%) and interchange them for tickets (here and here), to the idea of reconverting a theatre company into a distributor of pornographic magazines (taxed at 4%) and exchange magazines for theatre tickets (here and here). Complaints remained since and, finally, VAT rates where cut from 21 to 10%, in June 2017 for all live performances and in July 2018 for cinema.

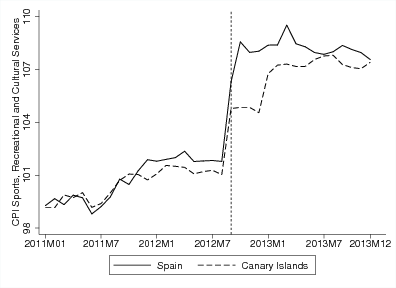

In the article published in the Journal of Cultural Economics, we conduct a research on the effect of the cultural VAT rise on the expenditure on cinema and performing arts of the Spanish households. By making use of quasi-experimental methods for causal inference, we are able to evaluate the change in household expenditure produced by the change in its indirect taxation, one of the most common cultural policies at the national level. This is possible because the cultural VAT reform did not affect all the territory of Spain equally; in the Canary Islands, that are excluded from VAT territory, the indirect taxation for cultural services just rose from 5% to 7%, and the increase in the tax rate happened on July 2012. The uneven change lead to a divergent evolution of prices for cultural services in those two areas, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

This natural experiment allows us to estimate the change in expenditure that can be directly attributable to the rise on cultural VAT, net from the effect of any other confounder. By making use of the data from the Spanish Household Budget Survey for the years 2011, 2012 and 2013, we describe the evolution of the expenditure on COICOP 09421, “cinema, theatre, opera, concerts, dance, circus, bullfighting and other light shows” for Peninsular Spain and the Balearic Islands and for the Canary Islands. The microdata from this survey also allow us to control for individual and household characteristics that are relevant to understand differences in cultural expenditure.

Figure 3:

We make use of a range of causal inference method to investigate the effect of the VAT change, and obtain our estimates making use of matching methods on the covariates that explain household expenditure on cultural services, after having obtained a difference in differences estimator that could be affected by the violation of the parallel trend assumption (as can be observed in Figure 3 above). As the subsample of the treated households (Peninsular Spain and Balearic Islands) is much bigger than the subsample of the untreated (Canary Islands), we estimate the average treatment effect on the untreated, finding no conclusive evidence of a change in the expenditure due to the VAT uneven rise. However, when we explicitly take into account that due to the VAT rise some households stopped spending on cultural services, we can observe that the overall effect is the result of the mixed effects of less households spending and a higher expenditure for those households that went on spending on cinema and performing arts. Our result is robust to different specifications and matching strategies and is consistent with placebo tests conducted on categories of cultural services that were not affected by that uneven change in indirect tax rates (museums and art galleries that went from 8 to 10% in the VAT Spanish territory, and from 5 to 7% in the Canary Islands).

We find that the average household expenditure on cinema and performing arts of the households in the Canary Islands would not have changed significantly, had they been exposed to the VAT rise. This average treatment effect is the results of two non-homogeneous responses. First, the tax rise would have reduced overall household cultural participation by means of attendance to cinema and the performing arts in around eight per cent (though this is not statically significant in some specifications). Second, those households that did not stop spending on cultural services would have increased their average annual expenditure about 52 euros. The increase of around 52 euros represents an increase of 18.5% with respect to the average expenditure of that group in 2011, which was 283.51 euros. This change is higher than the VAT increase itself, which rose 13 percent-age points (8–21%).

This finding can be interpreted in different ways. First, we get evidence of heterogeneous behaviour in the Spanish population. While some household have a small degree of attachment to cultural services and the effect of the VAT increase was to stop spending on them, some others exhibit an “enthusiast” or “activist” behaviour, as they increased the expenditure in a higher magnitude than the tax increase. Second, our results provide additional arguments to the debate against reduced rates for cultural goods and services that are claimed to distort relative prices and create tax incentives for the sectors with different rates (O’Hagan) suggests that governments should avoid fallacious demand-side arguments that claim that indirect tax reductions lead to a situation where cultural goods become affordable to everyone (Van der Ploeg). In any case, there is enough evidence that education is a much better predictor of participation in the arts than income and that education is very much related to the most important barrier for engagement, which is the lack of interest, so governments should consider both educational policies as well as fiscal incentives to promote access to culture.

References:

O’Hagan, J. (2011). Tax concessions. In R. Towse (Ed.), A handbook on cultural economics, 2nd edition. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar

Van der Ploeg, F. (2006). The making of cultural policy: A European perspective. In V. A. Ginsburg & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 1, pp. 1183–1221). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

About the authors:

Victoria Ateca-Amestoy, University of the Basque Country, UPV/EHU

Javier Gardeazabal, University of the Basque Country, UPV/EHU

Arantza Ugidos, University of the Basque Country, UPV/EHU

The article is based on:

Ateca-Amestoy, V., Gardeazabal, J. & Ugidos, A. On the response of household expenditure on cinema and performing arts to changes in indirect taxation: a natural experiment in Spain. J Cult Econ (2019) doi:10.1007/s10824-019-09357-0

Image source:

https://gulfbusiness.com/revealed-countries-highest-vat-rates/

Leave a Reply