By Michela Giorcelli and Petra Moser

Copyrights establish intellectual property rights in creative goods, from literature and science to images, film, and music. This work shows that the introduction of copyrights increases the quantity and the quality of creative output. Copyright extensions beyond the life of the original creator, however, have minimal effects on creativity.

Copyrights establish intellectual property rights in creative goods ranging from literature and science to images, film, and music. Almost all countries have established copyright laws. According to U.S. law, “the primary purpose of copyright law is to foster the creation and dissemination of intellectual works” (General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Laws 1961, p.5). Yet, little is known about the effects of copyrights on creativity, given the difficulty of finding systematic data on individual creative output at the time of copyrights introduction.

To circumvent these issues, in Giorcelli and Moser (2020) we study the effects of copyrights on creativity using a unique historical episode: Napoléon’s military victories in Italy. In 1796, Napoléon began his Italian campaign and two Italian states, Lombardy and Venetia, were annexed and formed the Cisalpine Republic. In 1801, the Republic adopted France’s copyright laws of 1793, granting composers exclusive rights for the duration of their lives, plus ten years for their heirs. In 1804, France replaced its system of feudal laws and aristocratic privilege with the code civil, a codified system of civic laws. The code left copyrights intact where they already existed but did not introduce them in states without copyright laws. As a result, only Lombardy and Venetia offered copyrights until the 1820s, while all other Italian states that came under French rule after 1804 had no copyrights, even though they shared the same exposure to French rule, as well as the same language and culture (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Map of Italy with Borders Established by the Congress of Vienna (1815)

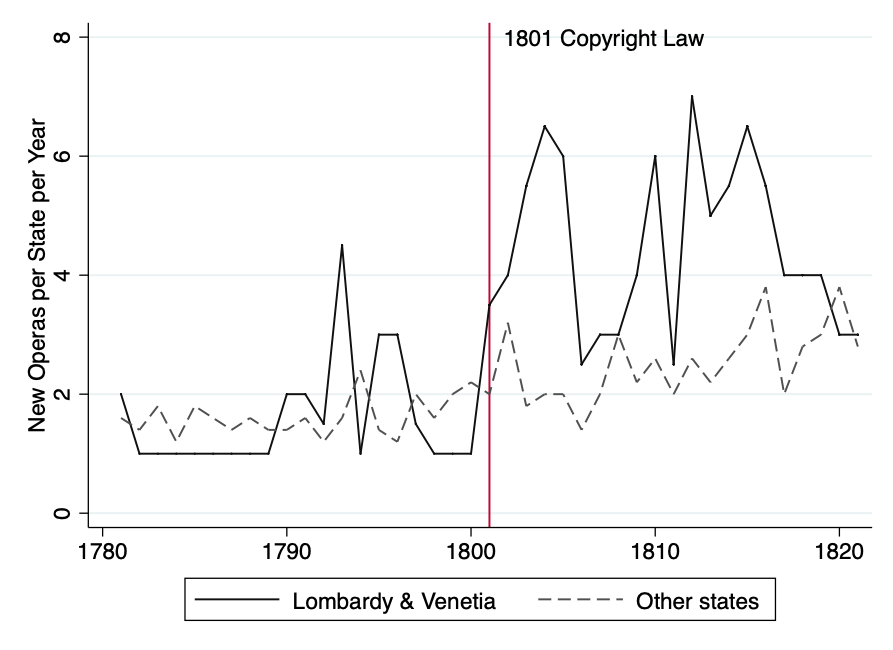

We analyze newly collected and digitized data on around 2,600 operas that composers created across eight Italian states between 1770 and 1900. A comparison in the number of new operas across Italian states with and without copyrights after 1801 indicate that the adoption of basic copyright laws led to a substantial increase in the creation of new operas. Lombardy and Venetia registered a 157-percent increase in operas production after 1801 compared with other Italian states without copyrights (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – New Operas per State and Year in Italy, 1781-1820

Notes: Data include 677 operas created in state i and year t between 1781 and 1820. Lombardy & Venetia adopted copyright laws in 1801. The control group Other States includes six remaining Italian states without copyrights: Sardinia, Modena and Reggio, Parma and Piacenza, Tuscany, Papal States and Sicily. Source: Giorcelli and Moser (2020).

In addition to influencing the number of new operas, copyrights may change the “quality” of creative work by encouraging composers to create pieces that are more profitable. Without copyrights, composers are only paid when they deliver the work, and derive no extra benefits from future performances. Copyrights, which grant composers the right to charge theaters every time they perform a piece, strengthen composers’ incentives to create works that are more popular and durable. Anecdotal evidence suggests that even star composers responded to these types of financial incentives. Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868), for example, announced that he would produce pieces that had “nothing new in them but the variations” (Beyle 1824, pp.200-201) when he felt that theaters in Naples paid too little for his operas.

Copyrights did in fact increase the “quality” of an opera, defined by its popularity and durability. We construct three complementary measures for these economically important differences in operas. Our first measure uses a standard reference of notable performances (Loewenberg 1978) to capture differences in the immediate historical success and popularity of an opera. The second measure identifies operas that were popular and durable enough to be performed at least once at the Metropolitan opera house in New York in the 20th and early 21st century. The third measure investigates the most durable operas that are still available for purchase on Amazon in the 2010s. Analyses for all three measures suggest that copyrights changed the quality of operas, by encouraging composers to create more popular and durable works.

Between 1826 and 1840, all remaining states adopted copyrights as part of Italy’s process towards unification. We find that these copyrights adoptions were associated with an increase in creativity. Copyright extensions, however, appear to have minimal effects on creativity, at best. In 1998 “Mickey Mouse” Copyright Term Extension Act increased US copyrights from the duration of the creator’s life plus 50 years to life plus 70 years. These extensions are set to expire in 2023, setting the stage for discussions on further increases in the length of copyrights. Compared with today, 19th-century extensions started from much lower levels, increasing copyrights from a base of the composer’s life, plus ten years for their heirs. Even in this setting, we find that extensions were associated by a decline in creative output. We use performance data to show that few pieces are durable enough to benefit from copyright extensions beyond their author’s life (Figure 3). In that case, the dynamic costs of long-lived copyrights for future creativity outweighs the benefits of longer terms.

Figure 3 – Performances in 100 years after Creation

Notes: Performances per year for the first 100 years since the premiere for 165 operas that premiered across Italy between 1781 and 1820 and entered Loewenberg’s (1978) Annals of Operas. Performances to the left of the vertical line would be on copyright under a regime of life + 10, which Lombardy and Venetia began to offer in 1801. The expected length of copyright under life + 10 equals 39.23 years: 10 years plus the expected remaining years of a composer of the average age at the time of the premiere. Please refer to Appendix Table A1 of Giorcelli and Moser (2020) for life table calculations.

To conclude, our research shows that short-lived copyrights can encourage creativity, measured both by the quantity and by the quality of newly created work. Yet, it is worth noting that copyright laws engender a critical tradeoff between the benefits of increasing pay for creative work today and the costs of restricting access for future generations. These dynamic costs of copyrights are especially damaging for fields in which new creativity depends on access to existing work. Despite recent advances (e.g., Biasi and Moser 2021 on the effects of copyright in science), more systematic theoretical and empirical research is needed to improve our understanding of these tradeoffs and how copyrights, more generally, shape creativity and innovation.

References

Beyle, Marie Henrie. 1824. The Life of Rossini. Printed for T. Hookham, Old Bond Street, by J. and C. Adlard, 23, Bartholomew Close. London.

Biasi, Barbara and Petra Moser. 2021. Effects of Copyright on Science. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 13(4): 218-60.

Loewenberg, Alfred. 1978. Annals of Operas (1597-1940). Oxford University Press. 3rd edition rev. and corrected. First published 1943; revised 1955. Oxford.

About this article

Giorcelli, Michela and Petra Moser. 2020. Copyright and Creativity: Evidence from the Italian Opera in the Napoleonic Age. Journal of Political Economy, 128(11): 4163-210.

About the authors

Michela Giorcelli is Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of California.

Petra Moser is Professor of Economics at the Stern School of Business, New York University.

About the image

The Barber of Seville (2015) Florida Grand Opera.

Leave a Reply